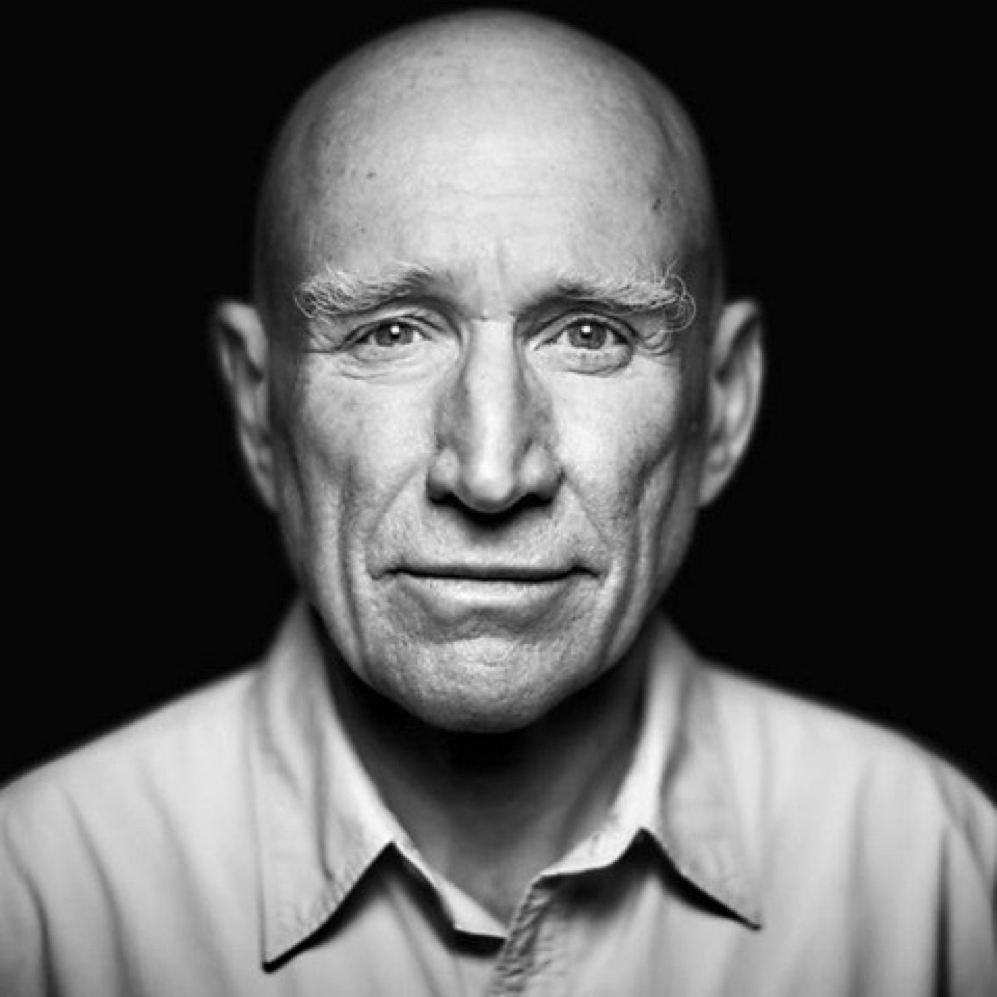

December 28, 2014 John Bailey, ASC

During the seemingly endless wars and humanitarian crises of recent decades, some “conflict” photographers have been accused of exploiting their helpless subjects, of purveying “poverty porn.” Doubtless, there are NGOs and other aid organizations that have found photographs of starving children and displaced people to be useful tools in their fundraising. Much of this photographic genre is merely serviceable imagery, but some of it, including the work of James Nachtwey and Sebastião Salgado, is not only closely observed and deeply emotional, but also representative of the highest aesthetic level of photographic art. And there’s the rub!

Critics like Susan Sontag and Ingrid Sischy have found it unseemly that the formal elements of good photography — composition, lens selection and light — should be exploited in photographing crises conditions, as if the photographer’s consideration of his own aesthetics were a kind of violation of his subject’s humanity. Perhaps no photographer of man’s displacements and sufferings has been more lauded or more criticized than Salgado, whose black-and-white images often evoke aching beauty in places of unbearable privation and violence. Sontag, in her book Regarding the Pain of Others and in a distilled article in The New Yorker on Dec. 9, 2002, employed the catchphrase “inauthenticity of the beautiful,” citing Salgado in blatantly judgmental terms.

Refugees at the Korem Camp, Ethiopia, 1984. (Photo: Sebastião Salgado) Born into an economically secure, land-rich, Brazilian family, Salgado, an avowed leftist, studied in São Paulo to become an economist and obtained a doctorate in Paris after he and his wife/lifelong collaborator, Lélia, fled Brazil’s right-wing military dictatorship. Salgado’s early work as an economist, under the aegis of the United Nations and World Bank related companies, took him to several African countries like Niger and especially Rwanda, where he began to take photos for himself in the early 1970s.

Earlier, he had borrowed his wife’s small camera to photograph her and theirfriends in Paris; in Africa, he realized what a powerful tool for social and economic change the camera could be. If Salgado’s critics bothered to trace the simple arc of his career, they could easily see the wellspring of his desire to become a photographer: a deeply held belief in the rights of man in the face of oppression and exploitation, a belief rooted in the political turmoil of his own homeland.

After he spent years as a photojournalist shooting for agencies such as Magnum and Sygma, Salgado gained enough financial independence to commit himself to his own photographic mission, work that began to define itself in complex and long-term photo essays that typically took a decade of intensive, often arduous, travel to remote parts of the earth. Edited by his wife, his work became books, beginning with Other Americas, followed by Sahel: The End of the Road, as well as large-scale traveling exhibitions, such as Workers, Migrations and Genesis: this most recent work is on display through Jan. 11 at the International Center of Photography. When Genesis closes, the ICP will move to a new location downtown.

Carol and I were first exposed to a large body of Salgado’s work in 1998 in Lisbon, where we saw an exhibition of Migrations, also known as Exodus, that had been designed by Lélia. It totally filled a newly open exhibition center and, along with a room of his portraits of children photographed at the same time as those of masses of displaced people, presented more than 300 images artfully hung and lit; it included a soundscape that changed from room to room. Salgado’s total commitment to documenting the humanity of his fellow man was irrefutable to anyone who saw this deeply moving exhibition.

By the mid 1990s, Salgado had photographed famine, war and genocidal atrocities in Rwanda, Sudan, Ethiopia, and the Congo, as well as internecine massacres in the former Yugoslavia: slaughter in Croatia, Bosnia and Serbia, in the heart of Europe: brutality among civilized cultures that left him shaken to the core, despairing of any hope for man.

Refugee Camp at Benako, Tanzania, 1994. (Photo: Sebastião Salgado) Later, while recovering from an auto-immune illness after completing the work for Migrations, Salgado returned to his family farm in the Brazilian state of Minas Gerais. He was convinced the sickness had been brought on by the horrors he had confronted in war zones, where he sometimes saw up to 10,000 people die in a day. In 2000, after beginning an intense land-recovery program on his family lands, Salgado traveled to France, to the remote village of Quincy in the Haute-Savoie, where he met and discussed the theme of the displaced people of Migrations with the great artist/critic/writer John Berger. Berger had been living on his farm for several decades in order to be among the people about whom he wrote. Berger is often called a “Marxist humanist,” and much of his work centers on the theme of the destructive effects of industrial capitalist economies on the lives of farmers and third-world peoples, something Salgado had seen up close, and on a global scale.

Berger and Salgado’s encounter, distilled into the 51-minute television documentary The Spectre of Hope, might appear on the surface to be a polemic, a rhetorical diatribe about the evils of the World Bank and globalization, both sharply defined as root forces of the displacement and poverty documented in Migrations. But both Salgado and Berger are deeply committed humanists, and their work in the service of their fellow man is a powerful testament to their authenticity.

In 2001, Berger wrote in The Guardian of Salgado’s work:

In a strange way, in all these pictures, one feels in Salgado’s vision the word ‘yes’ — not that he approves of what he sees, but that he says ‘yes’ because it exists. Of course he hopes that this ‘yes’ will provoke in people who look at the pictures a ‘no,’ but this ‘no’ can only come after one has said, ‘I have to live with this.’ And to live with this world is first of all to take it in. The opposite is indifference.

Near the end of the documentary, after the grim images of broken families, Berger asks Salgado about his portraits of children. Salgado explains that he made a pact with all the curious children who followed him as he worked: he would take their pictures, if they would first let him move freely to do his work. The images in the resulting book, Children, are not simple emoluments to appease these young people, but deeply affecting images of inocence where hope may still live. A montage of these portraits ends the film almost with an unspoken promise, one that is articulated by Salgado when he says he accepts that photos and books will not change the reality they depict, but they are at least what he can do — to begin.

In the midst of this celebratory season of Christmas and the New Year, with its sense of family and renewed promise, I hope you can set aside an hour to watch this deeply moving conversation between two articulate and humane men, sitting around the kitchen table in a rural farmhouse and reflecting on the condition of man as they consider images taken by the preeminent photographer of indigenous people.