January 25, 2015

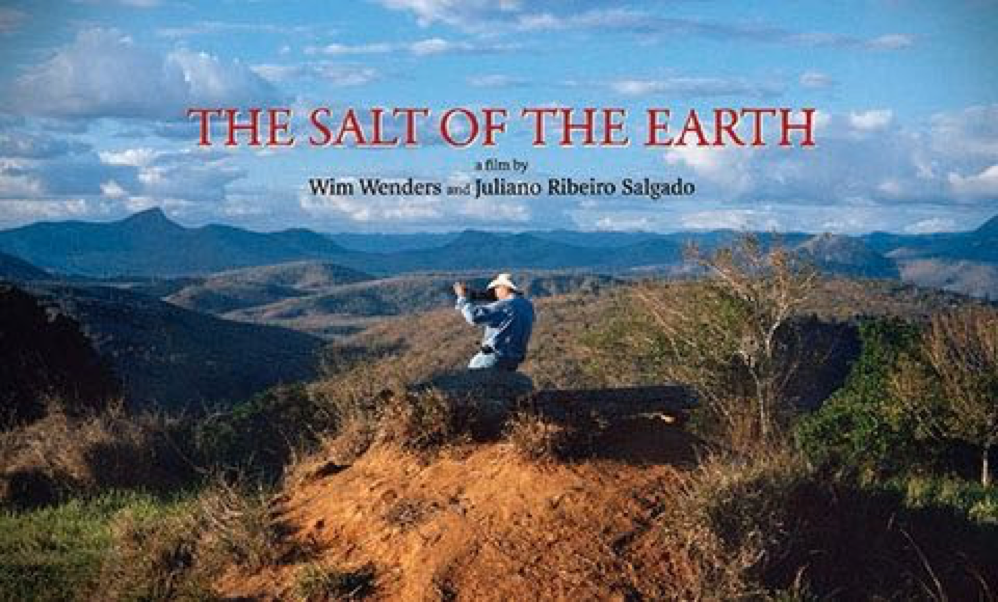

Sitting on the terrace outside his room at the Beverly Wilshire Hotel, Juliano Salgado, son of Brazilian photographer Sebastião Salgado, pulls down on his cigarette as the day turns to night and the Christmas lights below come to life. Juliano is only a few hours away from attending the IDA Awards, where he’ll represent the nominated feature documentary The Salt of the Earth, which he and Wim Wenders have made about Sebastião’s life and work. A few days before, the film was shortlisted by the Academy’s documentary-nominating committee; it has since been nominated in the Documentary Feature category.

Juliano has flown in from Berlin and is scheduled to leave the next day for São Paolo. Even on a tight schedule, he is meeting with me to discuss the film and how he, an experienced documentarian himself, and Wim Wenders had worked together to bring his father’s life and work to an audience that knew the photographer mainly through his powerful, often disturbing images — or those who did not know his work at all.

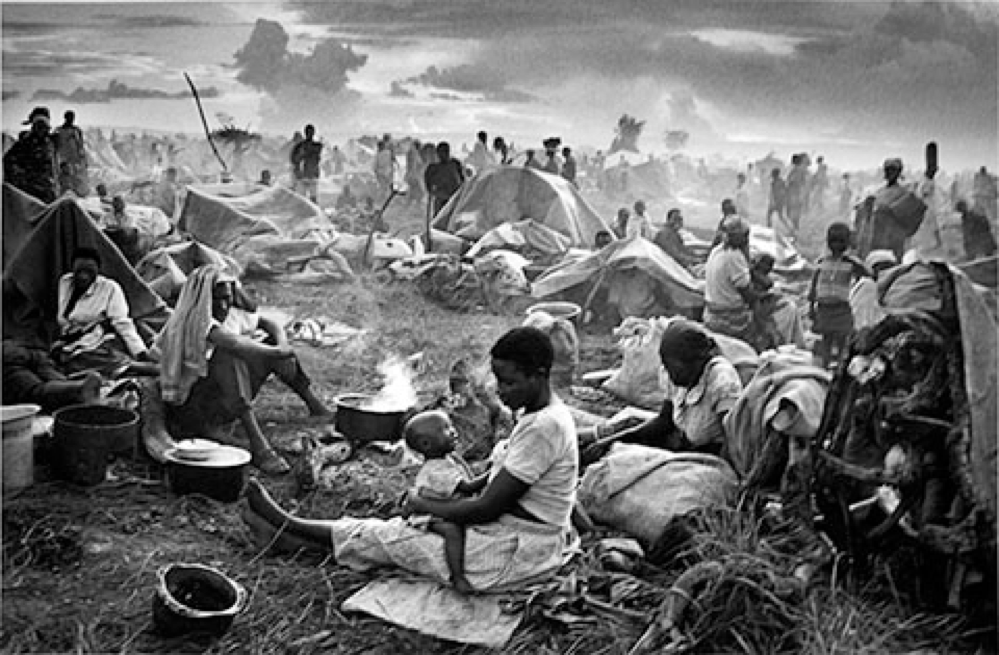

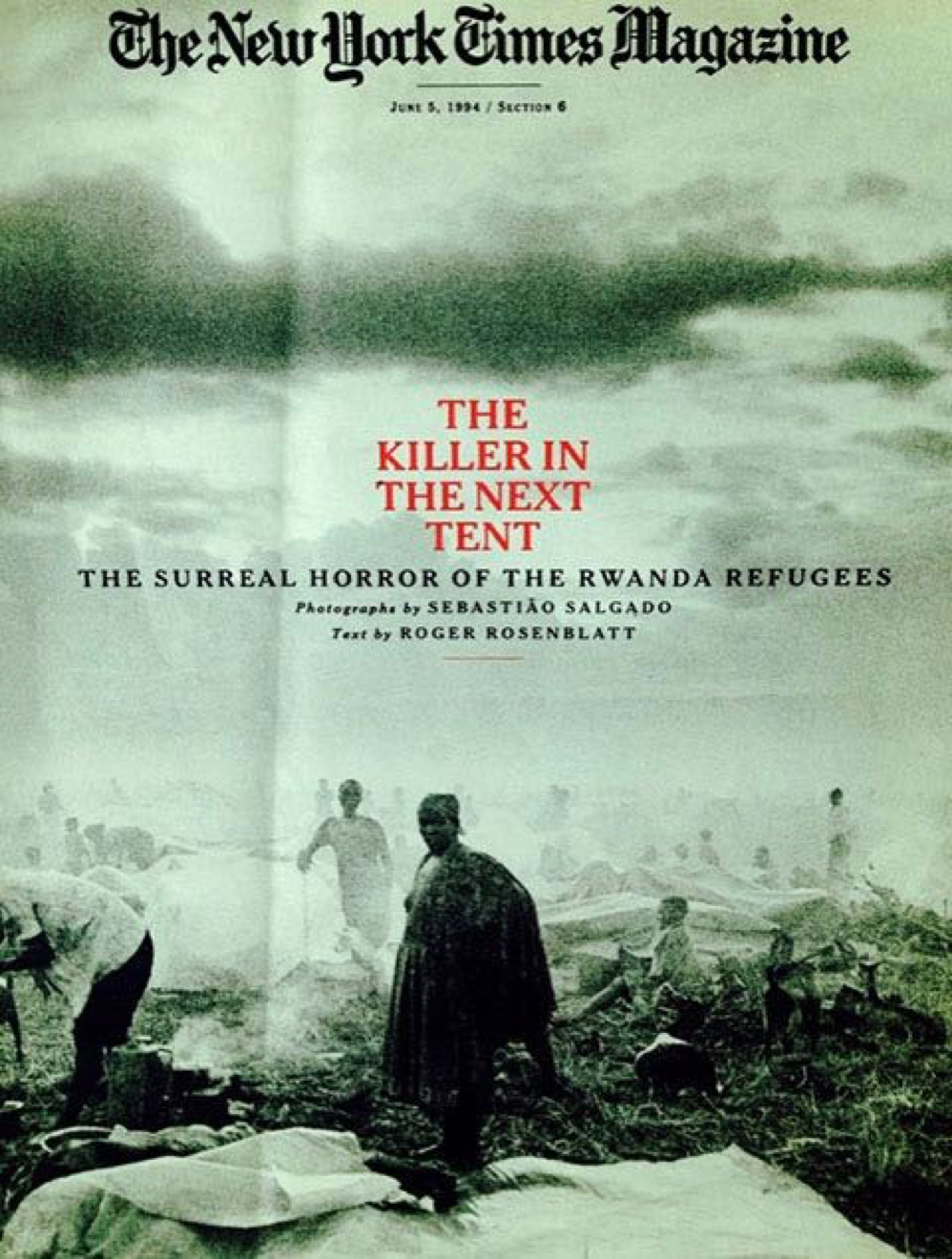

Juliano was born in 1974 in Paris, where his father and his mother, Lélia, had moved from Brazil to escape the authoritarian military government of their homeland. Throughout Juliano’s childhood, and even his teen years, his experience of his father was often fitful. Sebastião traveled and worked for more than 20 years in the world’s most conflict-ridden and poverty-stricken hotspots, amassing a body of work that followed his own imperatives rather than those of an assignment bureau. His return to Rwanda (a country he knew well from his early work for international coffee and tea companies) during the spring genocide of 1994, and then a year later in its aftermath, brought Salgado to the edge of psychic and physical collapse.

In The Salt of the Earth, Salgado talks of going into Rwanda during the 1994 genocide, and of the Tutsis’ subsequent pursuit of Hutus, which pushed many into the DRC border town of Goma on the shore of Lake Kivu. There, 2 million people, including many of the killers, had sought refuge. Looking into that heart of darkness, Salgado says, “We [humankind] didn’t deserve to live; no one deserved to live. When I left there I no longer believed in anything.” Wenders adds in voiceover, “What was there left for him [Salgado] to do after Rwanda?”

It was in the following years, as Juliano started to forge his own life in filmmaking, that father and son truly found each other. Reclamation of the family’s Brazilian lands helped to heal the elder Salgado, who decided in 2003 to embark on a new body of work, Genesis. His goal was to document remote, untamed lands around the world and the indigenous peoples who inhabit them — people who have nevertheless forged tightly knit extended families.

Juliano had been shooting video of the restoration of the family lands and had interviewed his mother and paternal grandfather (who, at 96, stood in once-fertile land that had become desert). Juliano had been thinking of making a film about his father’s work, but the plan was still mostly inchoate when his father invited him to join him in a series of photographing ventures connected to the Genesis project. Juliano says, “I wanted to find out who that man was, the man I knew as my father.” He continues:

When, in 2004, he embarked on his latest long-term project, this quest for unspoilt paradises which took up eight years, he suggested that I accompany him. I was reticent; I didn’t know how my work would fit in with him. But our first trip turned out to be incredible. It took us to Brazil, to the heart of Amazonia, some 300km from the nearest town, to meet an isolated tribe, the Zo’é, with whom we stayed for a month. These are people who still live in the Paleolithic era. I experienced that as a privilege, a moment suspended in time.

Juliano continues:

And a dialog formed between my father and I; or rather, re-formed. We then went to Papua New Guinea, to Irian Jaya, to stay with another isolated tribe, the Yali …… then to an island in the Arctic Circle, Wrangell, home to walruses and polar bears. During these journeys, we talked about a lot of things which we’d never talked about before, and that’s when I found a clear purpose to the footage I had been filming since I started accompanying him. When my father saw the first raw edits I had done with those pictures, he got very moved, to the point of having tears in his eyes.

Here is the French trailer for The Salt of the Earth, which begins with Salgado seeking out the Yali people of New Guinea. The English speaker is Wenders.

Eventually, Juliano realized he was much too close to the events and life of his father to be a dispassionate filmmaker, a perspective he felt was crucial to make the best film. His father had met Wenders five years earlier, and Wenders had expressed interest in making a film about Salgado. Wenders recalls that he had encountered Salgado’s images of the Serra Pelada open- pit gold mine years earlier in a Los Angeles gallery:

I have known Sebastião Salgado’s work for almost 25 years. I’d acquired two prints, a long time back, which really struck a chord with me and moved me. I framed them, and ever since they have hung over my desk. Inspired by these photographs, I visited an exhibition called ‘At Work’ soon after that.

Ever since then, I’ve been an unconditional admirer of Sebastião’s work.

Wenders intended to trek with the Salgados on several of their missions. He recalls,

Juliano had already accompanied his father on several trips around the world, and there were hours and hours of documentary images. I’d planned to accompany Sebastião on at least two ‘missions’ — in the great north of Siberia and in a balloon expedition over Namibia — but we had to cancel that because I fell ill and couldn’t travel. So instead, I started to concentrate on his photographic work, and we recorded several interviews in Paris. But the more I discovered his work, the more questions I had.

Here is an excerpt from the film in which Salgado shows the Yali the portraits he is making of them:

Juliano met with Wenders to discuss how they would work together. Juliano says:

I showed Wim what I had filmed during the trips with my father and explained how I felt these images had to be linked to Sebastião’s trajectory so that we could learn from his testimony, his memories, the situations in which he had found himself. This discussion resulted in the emergence of the structure of our film, but for my part … I was incapable of having the necessary distance to achieve this. Wim Wenders was now there to pull together this story of a man who had grown weary of the suffering he had photographed, who himself bears the scars of what he has seen and experienced, and who said: ‘After years working in refugee camps, I had seen so much death that I felt myself dying.’ To begin with, I thought that Wim and my father would sit either side of a little table and would talk. Not so. Working with a great artist like Wenders changes things, and the idea he came up with to confront Sebastião visually with his memories is much more ingenious.

Wenders describes the interviews with the senior Salgado:

During the first interviews, I appeared on camera, but as our conversations progressed, I increasingly had the feeling I should disappear, and that I should give the whole space over to Sebastião and, above all, to the photographs. The work should be left to speak for itself. So I had the idea of a directorial approach using a sort of dark room: Sebastião was in front of a screen, looking at the photographs, whilst answering my questions about them. So the camera was behind this screen, filming through his photographs — if that’s how I can put it — thanks to a semi-transparent mirror, which meant that he was looking at the same time at his photographs and the spectator. I thought it was the most intimate setting for the audience to hear him express himself and at the same time discover his work. We more or less cut out all the ‘traditional’ interviews, of which only a few bits remain.

The Salt of the Earth is unlike any bio-documentary you’ve seen. It is not just observed; it’s lived in the emotional space of Salgado himself as he looks at his images and, prompted by Wenders (also an artist of deep insight and emotion), relates to us the moments captured by each image at 1/250th of a second. It is all also informed by the participation and insight of Juliano, who shares Sebastião’s breath and blood. The resulting film is a record of lived life at the edge of pain and loss, and a document of how one man came out at the other end and found in nature itself the strength to move on. Salgado says, “The main thing was to understand that I’m as much a part of nature as a turtle or a tree, or a pebble.”

And Salgado’s mission will continue in the work of his son.